The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expands health insurance coverage by offering both penalties and incentives. Low and middle income households who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid can purchase subsidized coverage on the health insurance marketplaces using premium assistance tax credits. Individuals who do not obtain coverage, through any source, are subject to a tax penalty unless they meet certain exemptions. The penalties under the so-called individual mandate were phased in over a three-year period starting in 2014 and are scheduled to increase substantially in 2016. A key area of uncertainty for 2016 is how much the increased penalties will encourage uninsured people – particularly those who are healthy – to obtain coverage, boosting enrollment in the marketplaces and improving the insurance risk pool. This analysis provides estimates of the share of uninsured people eligible to enroll in the marketplaces who will be subject to the penalty, and how those penalties are increasing for 2016.

People are generally required to be covered by a health insurance policy which meets minimum standards or pay a tax penalty.

Some individuals are exempt from the penalty, including undocumented immigrants, those whose incomes are so low that they are not required to file taxes, people with incomes below 138% of poverty in the “Medicaid gap” in states that have not expanded eligibility for Medicaid under the ACA, people who have to pay more than 8.13% of household income for insurance (taking into account any employer contributions or subsidies) and certain individuals who have membership in certain groups or face a particular hardship.

For those who are uninsured and do not meet one of the exemptions, the penalty for 2016 is calculated as the greater of two amounts:

The penalty can be no more than the national average premium for a bronze plan (the minimum coverage available in the individual insurance market under the ACA), which was $2,484 in 2015 for single coverage and $12,420 for a family of three or more children. The penalty is pro-rated for people who are uninsured for a portion of the year and waived for people who have a period without insurance of less than three months.

As the table below shows, the penalty amounts have increased substantially since 2014.

| Table 1: Penalties Under the Individual Mandate | ||||||

| Year | Percent of Income (%) | Per Adult Penalty ($) | Household Penalty ($) | Prior Tax Year Filing Threshold Individual under 65 ($) | Prior Tax Year Filing Threshold – Married filing jointly under 65 ($) | Affordability Standard (%) |

| 2014 | 1 | 95 | 285 | 10,000 | 20,000 | 8 |

| 2015 | 2 | 325 | 975 | 10,150 | 20,300 | 8.05 |

| 2016 | 2.5 | 695 | 2,085 | 10,300 | 20,600 | 8.13 |

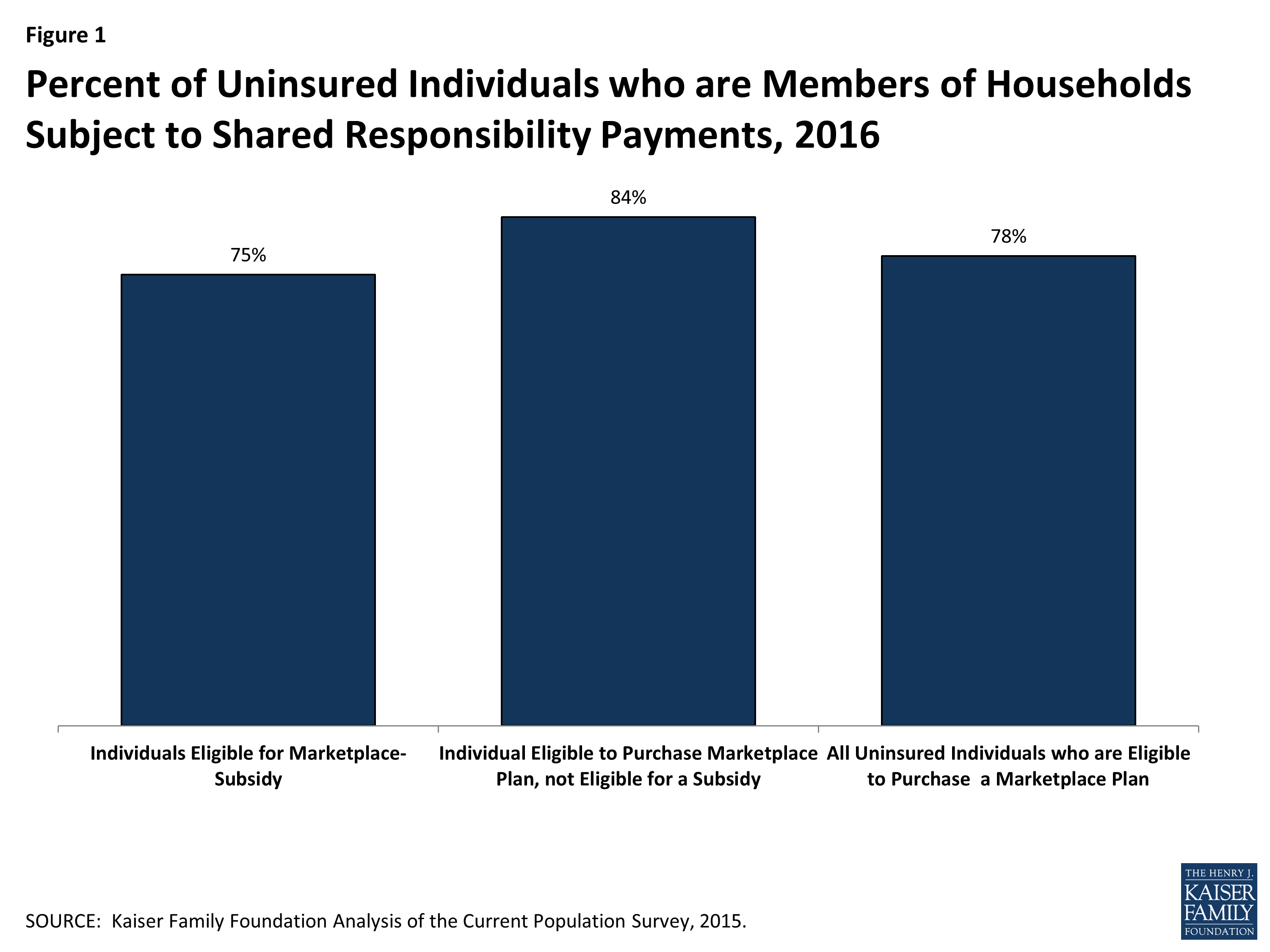

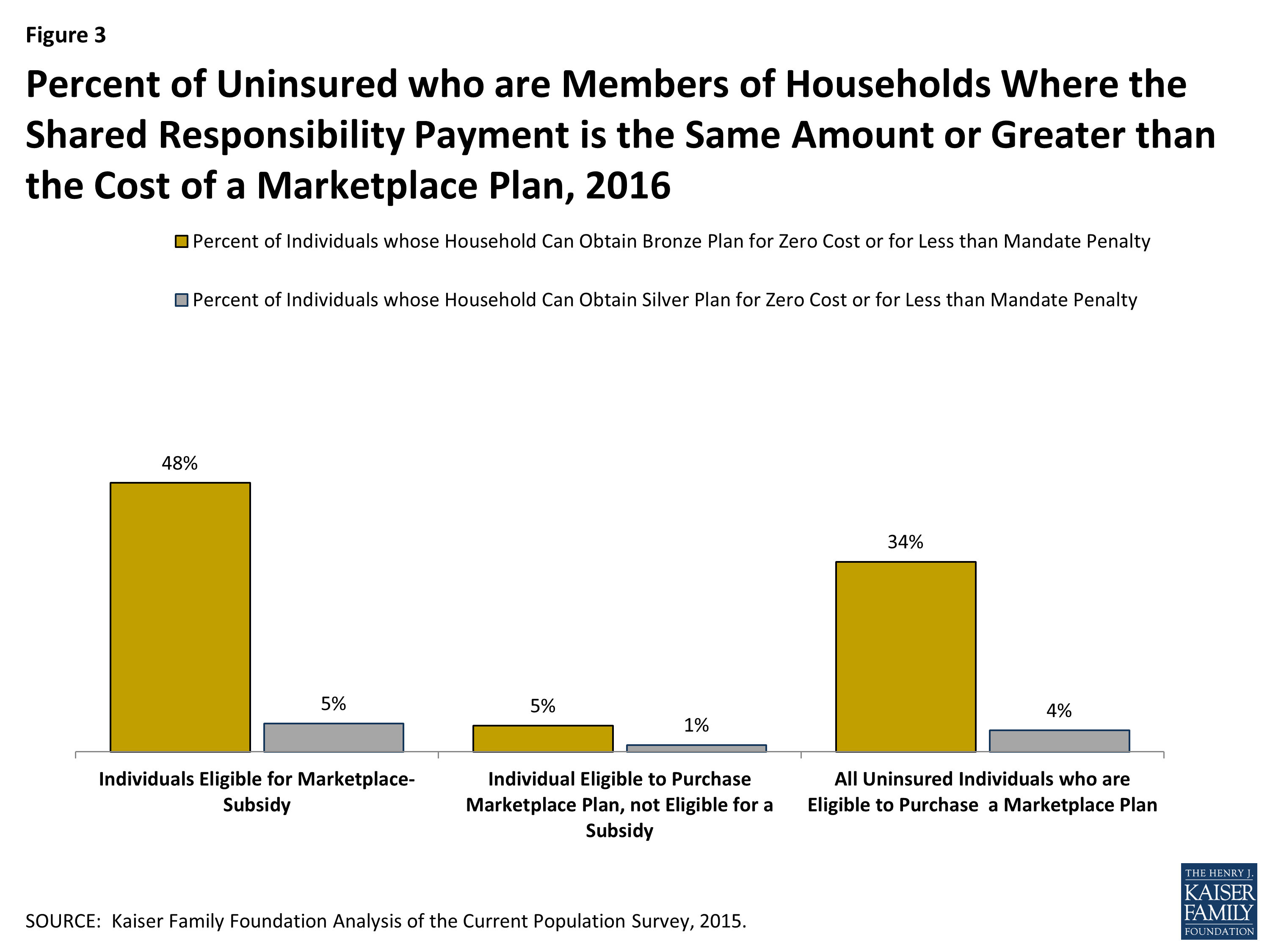

To assess how effective the individual mandate may be in increasing marketplace enrollment, we looked at how penalties are increasing for people who were uninsured in early 2015 and are “marketplace eligible.” This includes non-elderly people eligible for marketplace subsidies as well as those who are not because their incomes are too high, but excludes people who are Medicaid-eligible, in the “Medicaid gap,” or eligible for employer coverage. 1 We estimate that 78% of people who are uninsured and marketplace eligible would be subject to the individual mandate penalty if they remain uninsured in 2016, including 75% of people who are eligible for premium subsidies and 84% of people who are not.

Figure 1: Percent of Uninsured Individuals who are Members of Households Subject to Shared Responsibility Payments, 2016

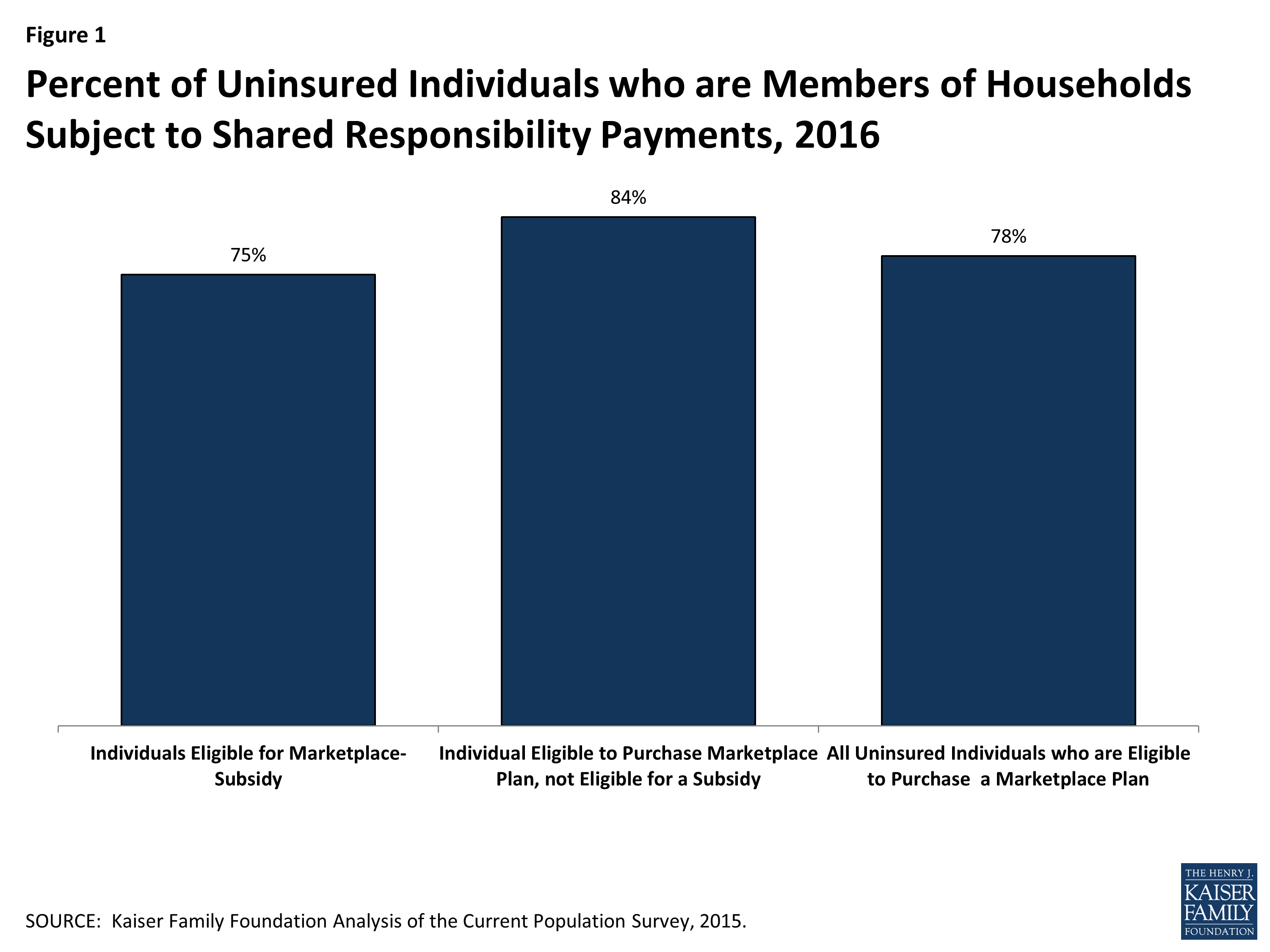

Among individuals who were uninsured in early 2015 and eligible to enroll in the marketplace, the average household penalty in 2016 is $969. This is up 47% from the average estimated penalty this year of $661. Those who are eligible for premium subsidies will face an average household penalty of $738 in 2016, while the average household penalty totals $1,450 for uninsured individuals not eligible for any financial assistance.

Figure 2: Among Uninsured Individuals, the Average Household Shared Responsibility Penalty, 2015-2016

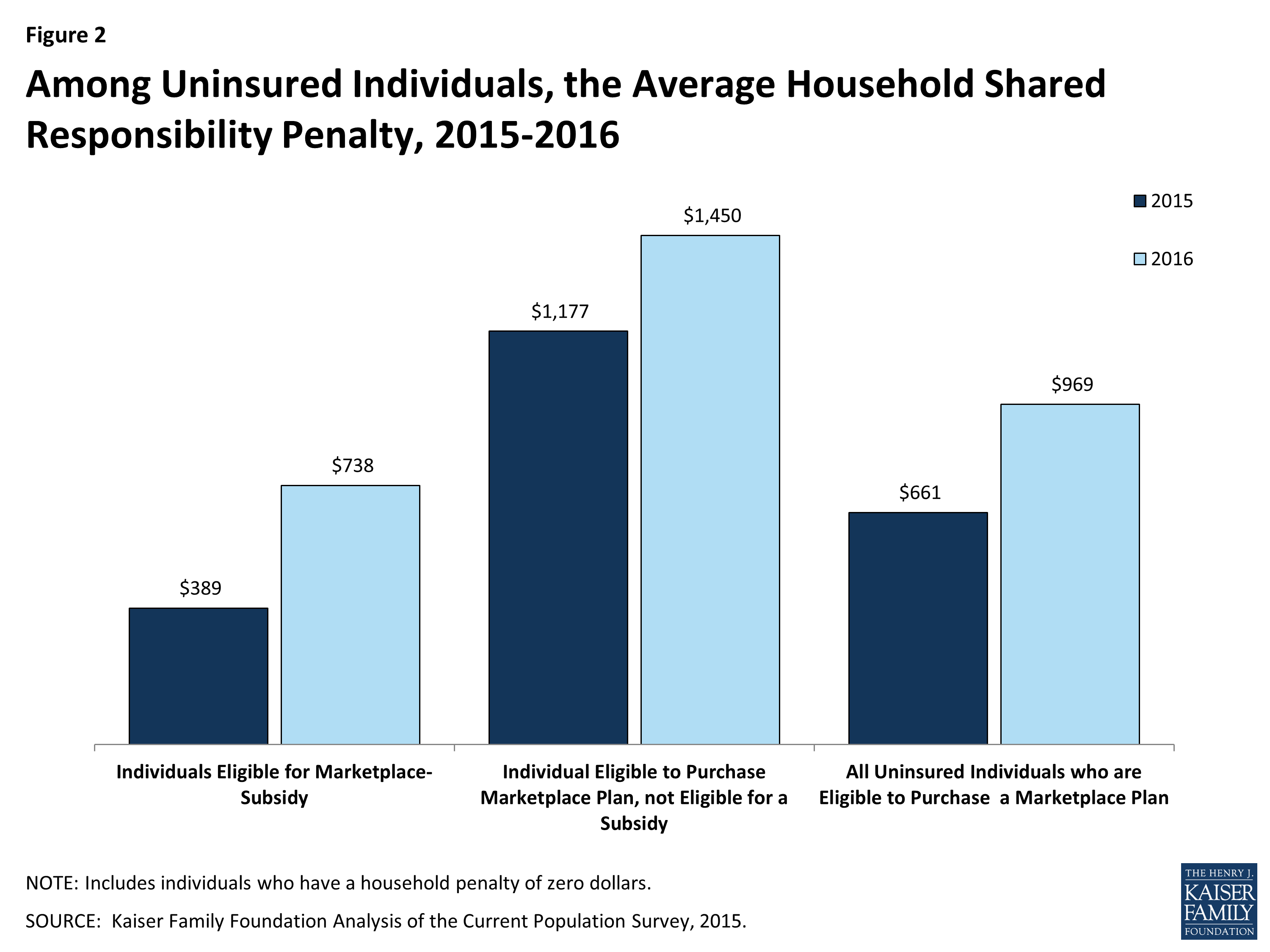

About 7 million uninsured people are eligible for marketplace premium subsidies and are a key target group for increasing marketplace enrollment. Almost half (48%) of them could, in fact, buy a bronze plan for a zero premium contribution or for less than the penalty they would owe for remaining uninsured, including 28% who could buy a bronze plan using their premium subsidy for a zero premium. In other words, 3.5 million subsidy-eligible uninsured people could either get coverage for free or end up paying less by enrolling in marketplace coverage than by remaining uninsured and paying the individual mandate penalty. However, bronze plans come with high deductibles and low-income enrollees may be better off financially enrolling in silver plans that have higher premiums but are eligible for cost-sharing subsidies.

Figure 3: Percent of Uninsured who are Members of Households Where the Shared Responsibility Payment is the Same Amount or Greater than the Cost of a Marketplace Plan, 2016

In total, out of almost 11 million uninsured people who are eligible to enroll in marketplace coverage either with or without financial assistance, 7.1 million would pay less for any penalty than they would to buy the least expensive insurance available to them.

Increasing enrollment in the ACA’s health insurance marketplaces would help to reduce the number of people uninsured and keep premium increases down as more healthy people sign up. Premium subsidies are an important “carrot” to attract new enrollees. As penalties grow in 2016, the “stick” of the individual mandate may also become an increasingly significant factor in the household decisions about whether to buy insurance.

However, the effectiveness of the individual mandate as a tool to increase enrollment will depend on how prominent a place it occupies in outreach messaging. And, emphasizing the mandate to obtain coverage presents challenges for ACA advocates since it is the most unpopular part of the law. At the same time, lack of knowledge about the increasing penalties under the mandate could lead to unpleasant surprises when people file their 2016 taxes in early 2017.

Matthew Rae, Cynthia Cox, Gary Claxton, and Larry Levitt are with the Kaiser Family Foundation. Anthony Damico is an independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

This analysis uses data from the 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). The CPS ASEC provides socioeconomic and demographic information for the United Sates population and specific subpopulations. Importantly, the CPS ASEC provides detailed data on families and households, which we use to determine income for ACA eligibility purposes.

The CPS asks respondents about coverage at the time of the interview (for the 2015 CPS, February, March, or April 2015) as well as throughout the preceding calendar year. People who report any type of coverage throughout the preceding calendar year are counted as “insured.” Thus, the calendar year measure of the uninsured population captures people who lacked coverage for the entirety of 2014 (and thus were uninsured at the start of 2015). We use this measure of insurance coverage, rather than the measure of coverage at the time of interview, because the latter lacks detail about coverage type that is used in our model. Based on other survey data, as well as administrative data on ACA enrollment, it is likely that a small number of people included in this analysis gained coverage in 2015.

Medicaid and Marketplaces have different rules about household composition and income for eligibility. For this analysis, we calculate household membership and income for both Medicaid and Marketplace premium tax credits for each person individually, using the rules for each program. For more detail on how we construct Medicaid and Marketplace households and count income, see the detailed technical Appendix A available here.

Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. Since CPS data do not directly indicate whether an immigrant is lawfully present, we draw on the methods underlying the 2013 analysis by the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC) and the recommendations made by Van Hook et. al. 2 , 3 This approach uses the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to develop a model that predicts immigration status; it then applies the model to CPS, controlling to state-level estimates of total undocumented population from Department of Homeland Security. For more detail on the immigration imputation used in this analysis, see the technical Appendix B available here.

Individuals in tax-filing units with access to an affordable offer of Employer-Sponsored Insurance are still potentially MAGI-eligible for Medicaid coverage, but they are ineligible for advance premium tax credits in the Health Insurance Exchanges. Since CPS data do not directly indicate whether workers have access to ESI, we draw on the methods comparable to our imputation of authorization status and use SIPP to develop a model that predicts offer of ESI, then apply the model to CPS. For more detail on the offer imputation used in this analysis, see the technical Appendix C available here.

The household contribution for a marketplace plan includes the cost of covering all subsidy-eligible individuals in the tax filing unit, including those who might currently be purchasing non-group coverage outside of the exchange. Individuals who are eligible for a Basic Health Plan in New York or Minnesota are included as subsidy-eligibles in this analysis. The penalty for each uninsured non-elderly individual is based on the number of uninsured people in the household. The cost of the average bronze plans in 2016 is estimated by inflating the 2015 average by the growth between 2014 and 2015. In this analysis, households with incomes below the relevant tax filing threshold, in the Medicaid gap, or where the cost of the cheapest available (subsidized) bronze plan exceeds the affordability standard are considered to not have a penalty. Individuals ineligible to purchase marketplace coverage, such as undocumented immigrants, are excluded from the analysis. There may be additional exemptions which individuals are eligible for, including particular hardships such as medical debt or domestic violence and membership in groups such as a health care sharing ministry or a recognized Indian tribe. Individuals 65 or above are excluded from the analysis.