Retinopathy is a medical term that means retina damage. There are many types of retinopathy, and each one happens for a different reason. People often develop retinopathy because of a health condition like diabetes, high blood pressure or a genetic disorder.

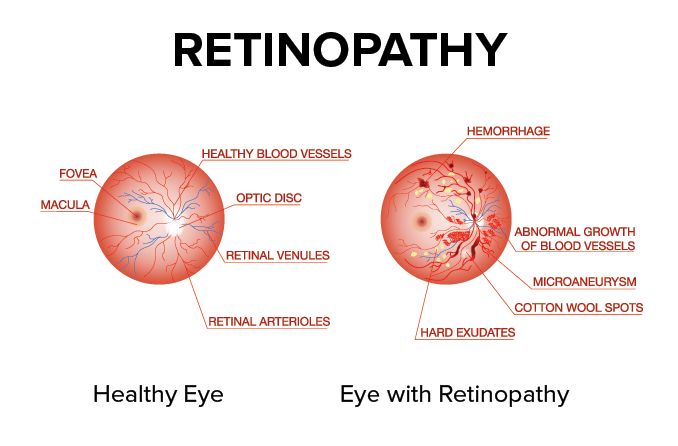

The retina is a thin layer of cells that lines the inner back wall of each eye. These cells react to light and send signals to the brain so you can see.

Retinopathy (reh-tuh-NAH-puh-thee) often means something is wrong with the blood vessels that keep your retina healthy and nourished. This can harm your eyesight, and certain conditions can lead to vision loss.

Some retinopathies can be slowed or prevented. Eye doctors may recommend lifestyle changes, medicine or surgery to help their patients keep the vision they have.

Retinopathy causes include:

Retinopathy symptoms can vary depending on which condition you have.

At first, you might not notice any changes in your vision. Many retinopathies don't cause noticeable symptoms until you start to lose some of your vision.

An eye doctor can see early signs of retinopathy during an eye exam and take action before it harms your eyesight. If you already have some vision loss, they may be able to stop it from getting worse.

When retinopathy causes symptoms, they might include:

It's important to remember that retinopathy symptoms can be very different from one type to the next.

Some symptoms happen suddenly, while some come on slowly. Others may come and go.

Talk to an eye doctor any time you notice changes in your eyesight. They can tell you if retinopathy is causing your symptoms.

Get medical help right away if you have sudden symptoms. These could be signs of an eye- or health-related emergency.

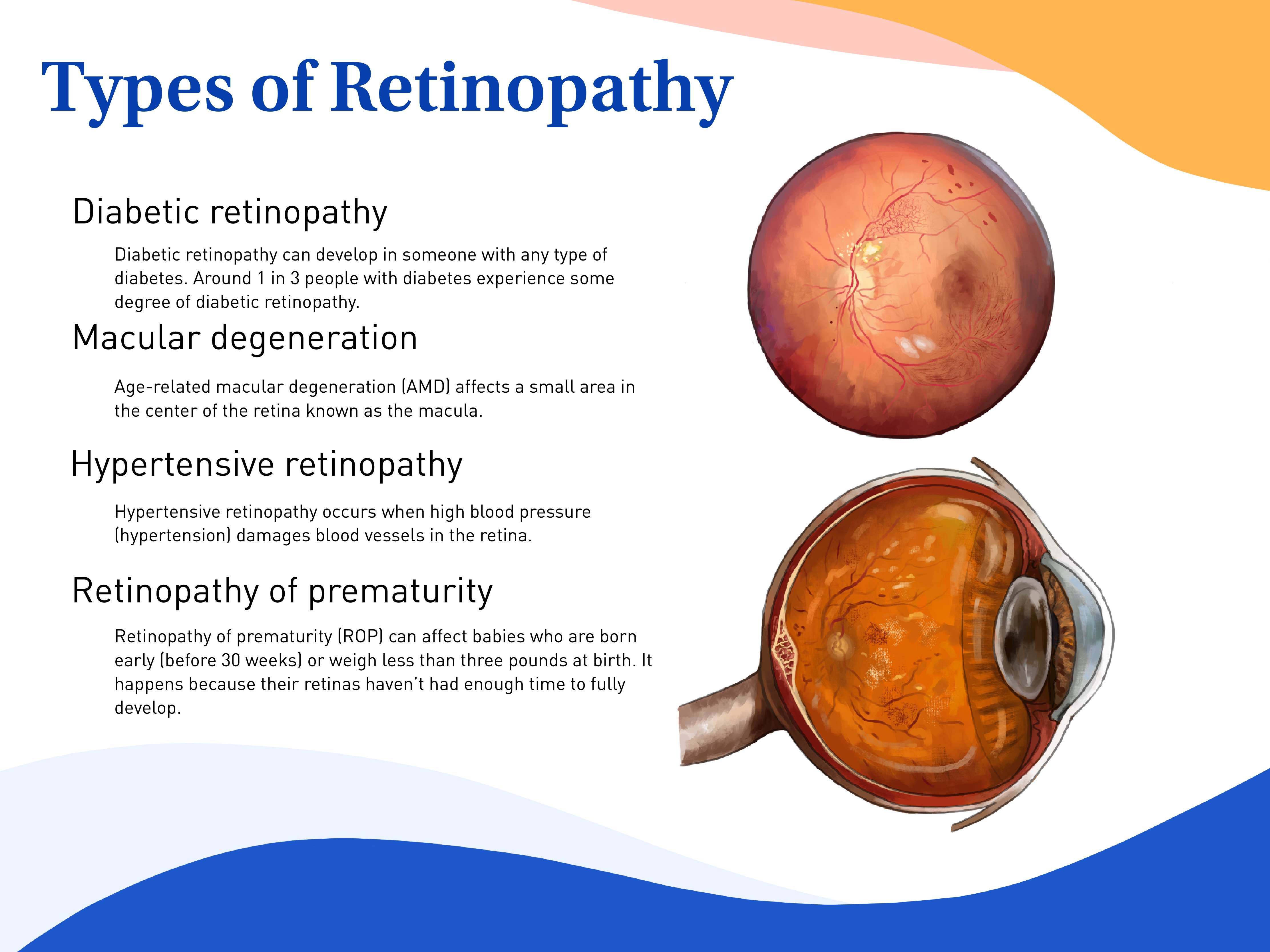

Retinopathy can happen for many different reasons. Some conditions improve on their own, but others need treatment. Specific types of retinopathy include:

Diabetic retinopathy can affect someone with any type of diabetes. About 1 in 3 people with diabetes have some amount of diabetic retinopathy.

Click image to enlarge.

There usually aren't any symptoms early on. As the condition gets worse, people may experience:

These usually happen in both eyes.

Someone with diabetes can prevent eye damage by keeping their blood sugar and blood pressure under control. Their eye doctor may also recommend eye injections or laser surgery.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) affects a small spot in the center of the retina, called the macula.

There are two types of AMD.

Dry AMD (the more common type) is when the macula gets thinner as you get older. Wet AMD is caused by unusual blood vessel growth.

Dry AMD doesn't cause symptoms early on — symptoms start in the middle or late stage. Wet AMD can only be late stage.

Click image to enlarge.

Eventually, both types can:

Lifestyle changes, supplements, eye injections and laser surgery can help some people slow or stop AMD.

Blood vessels in your eyes can get partially or totally blocked, just like they can in other parts of your body. The medical word for a blockage is occlusion.

Branch retinal vein occlusion is one of the most common kinds of retinopathy. It happens when a small vein is blocked and can't carry blood away from the retina.

A retinal artery occlusion makes it harder for blood to reach the retina. Some people call this an "eye stroke."

Retinal artery and vein occlusions can cause sudden vision loss, blurry vision and other symptoms. They almost always happen in one eye.

Permanent vision loss can happen quickly, so retinal occlusions need to be treated right away. There are several emergency treatments doctors can use to help save your vision.

Central serous chorioretinopathy (cor-ee-oh-reh-tuh-NAH-puh-thee) happens when fluid leaks from the choroid, a thin layer below the retina. Males in their 30s, 40s and 50s are most at risk, especially during periods of high stress.

It can affect one eye (more common) or both.

This retinopathy can cause symptoms such as:

Central serous chorioretinopathy often goes away within a month or two. Eye doctors can use medication, laser treatment or a form of light therapy to help more severe cases.

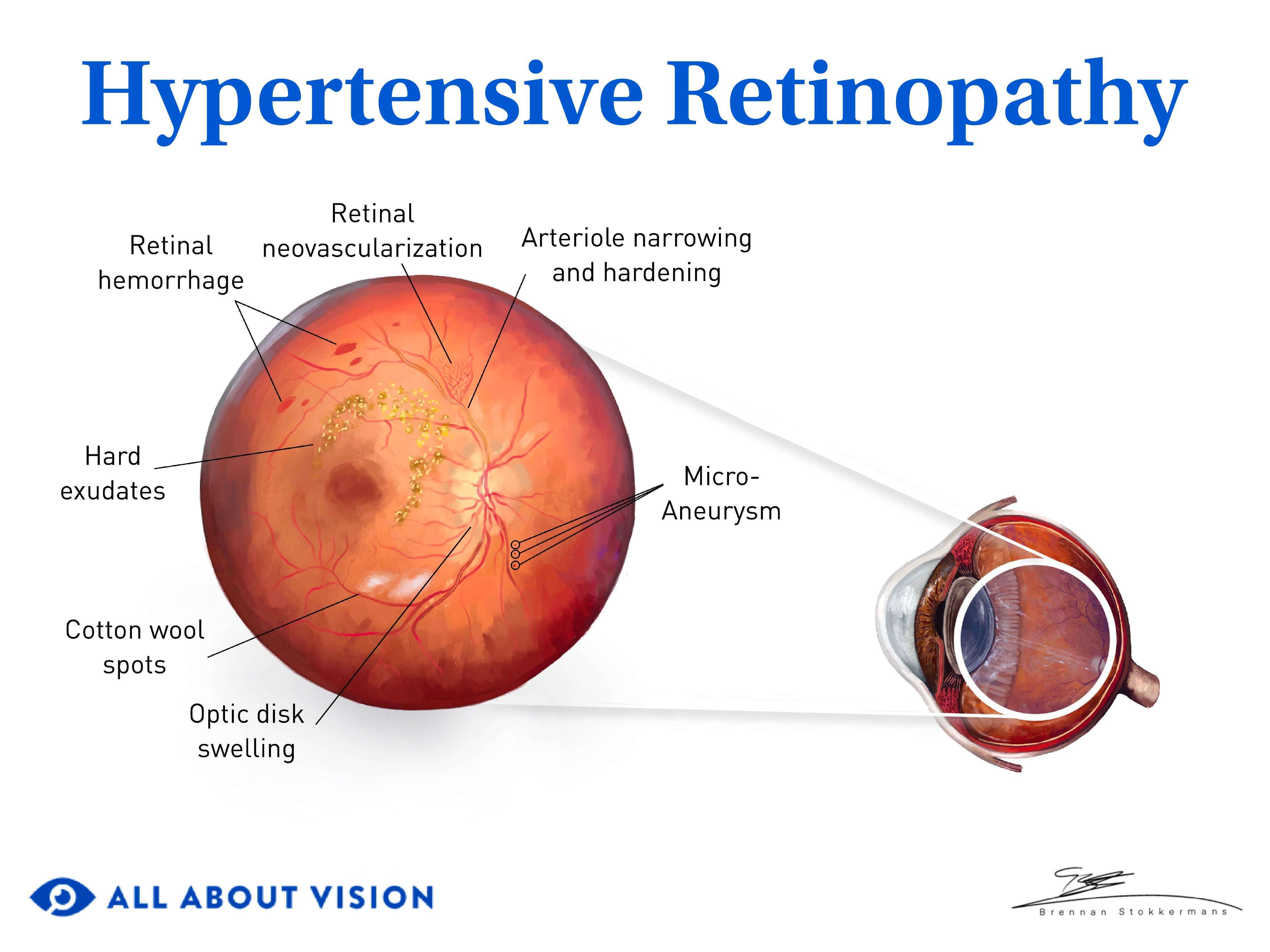

Hypertensive retinopathy is another common form of retinopathy. It happens when high blood pressure (hypertension) damages the retina's blood vessels.

People have a higher risk for retina damage the higher their blood pressure is and the longer it stays high.

Click image to enlarge.

Hypertensive retinopathy usually won't cause symptoms until it gets worse. Then it can cause:

Sometimes, the symptoms will go away once your blood pressure is normal.

Controlling high blood pressure is the only proven way to prevent and treat hypertensive retinopathy.

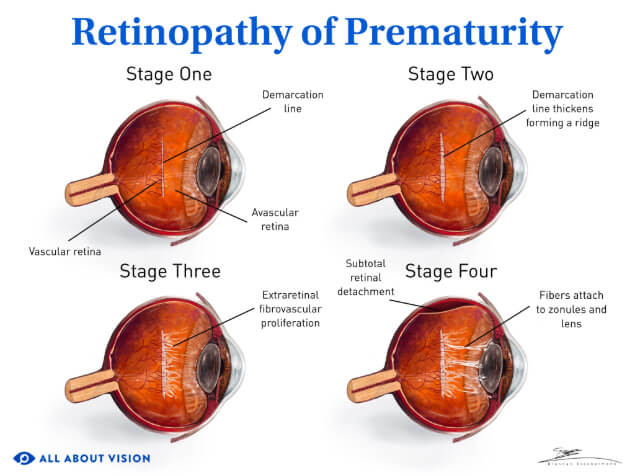

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) can affect newborn babies who are born early (before 30 weeks) or weigh less than three pounds when they're born. It happens because a baby's retinas haven't had enough time to develop all the way.

Click image to enlarge.

ROP doesn't cause obvious symptoms at first, but a baby may eventually show signs of retinopathy. These can include:

Sometimes mild ROP gets better on its own. Severe or worsening ROP may need to be treated with eye injections or surgery.

Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy is retina damage caused by the medication hydroxychloroquine (brand name Plaquenil). The drug was initially used to treat malaria, but it is now mostly used to treat certain autoimmune diseases.

Most people with this kind of retinopathy have taken hydroxychloroquine for many years or at high doses.

As the condition progresses, it can cause:

The only proven way to stop eye damage is to stop taking hydroxychloroquine. If needed, doctors can help patients find different ways to treat their underlying health conditions.

Sickle cell retinopathy can happen when someone has sickle cell disease. The genetic disorder causes misshapen red blood cells that die off earlier than they should, which can lead to health and eye problems.

The C-shaped cells can bunch together and block blood vessels in the retina. That can make new blood vessels grow in unusual and potentially dangerous ways.

Many people with sickle cell retinopathy don't have symptoms. But some people experience:

An eye doctor may suggest laser treatment to prevent future damage. Some people may have eye injections to stop new blood vessels from growing.

Solar retinopathy is when too much ultraviolet (UV) radiation hurts your retina. In most cases, this happens when someone looks at the sun without the right protection.

Researchers haven't found an effective way to treat solar retinopathy. The vision problems often improve on their own within six months, but some damage may be permanent.

Solar retinopathy is different from an "eye sunburn." This condition (called photokeratitis) can be painful, but it only affects the outer layer of your eye and usually gets better within a few days.

Exposure to a lot of radiation can damage your retina. Doctors call this radiation retinopathy.

Higher doses of radiation usually equal a higher risk of retina problems.

Radiation cancer treatments are a common cause of radiation retinopathy. The damage is more common when radiation is aimed at an area around the eyes or nose, especially when it's impossible to protect the eye.

People won't always notice early or mild symptoms. If there's a lot of damage, someone may see eye floaters or feel like their vision is worse overall.

Eye doctors can use certain oral medications, eye injections and laser procedures to help treat this problem.

Some retinopathies aren't as widely known as others, but they are just as important for people affected by them. Some of these conditions are:

There are more types of retinopathy than the ones listed above. An eye doctor will use a comprehensive eye exam to diagnose their patient or refer them to a specialist.

Eye doctors need to perform a dilated eye exam to diagnose any kind of retinopathy.

During this exam, the doctor will use eye drops to make your pupils open wider. It doesn't hurt, but it can make your vision blurry and your eyes sensitive to light for a few hours.

Your doctor may give you temporary sunglasses to wear, but you can use your own pair, too.

Retinopathy treatment depends on which type of eye problem you have and other eye or health factors.

Sometimes, retinopathy needs to be managed or treated to prevent more vision loss. Some people need immediate treatment, but other people can wait a while. This depends on your condition and how severe your doctor thinks it is.

For some retinopathies, doctors will recommend an eye treatment like laser surgery, eye injections or other procedures. But the treatment doesn't always involve your eyes. In these cases, your doctor could suggest taking medicine by mouth or making adjustments in your everyday life.

Some kinds of retinopathy don't have any treatment. They may or may not get better on their own.

If retinopathy is caused by a whole-body disease like diabetes or high blood pressure, controlling the disease may prevent future damage to your retina. Your doctor can help develop a plan to manage your eye health and overall well-being.

If your eye doctor sees any signs of retinopathy, they may refer you to a retina specialist — an ophthalmologist (medical eye doctor) who's specifically trained to diagnose, treat and manage retinopathy.

Schedule an eye exam with a nearby eye doctor if you notice any changes in your eyes or eyesight.

Some eye problems aren't always symptoms of retinopathy. They could be signs of a refractive error like nearsightedness, an eye infection or another eye condition altogether.

If your doctor sees signs of retinopathy, they may be able to recommend treatment to help protect your vision for the future.

Retinopathy. StatPearls [Internet]. August 2023.

Retinopathy. Harvard Health Publishing. September 2023.

Blood vessels. Cleveland Clinic. July 2021.

Sickle cell retinopathy. Retina Health Series. American Society of Retina Specialists. 2020.

Diabetic retinopathy. National Eye Institute. February 2024.

Macula lutea. A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. November 2023.

Eye stroke. Cleveland Clinic. September 2022.

What is a retinal vein occlusion? EyeSmart. American Academy of Ophthalmology. February 2024.

What is a retinal artery occlusion? EyeSmart. American Academy of Ophthalmology. August 2023.

Retinal vein occlusion. A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. January 2024.

What is central serous chorioretinopathy? EyeSmart. American Academy of Ophthalmology. November 2023.

Retinopathy of prematurity. National Eye Institute. November 2023.

Hydroxychloroquine toxicity. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. December 2023.

Hydroxychloroquine. AHFS Patient Medication Information. October 2023.

Prevention and treatment of SCD complications. National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC. July 2023.

Solar (photic) retinopathy. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. August 2022.

Solar retinopathy. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. December 2023.

Brain map frontal lobes. Queensland Health. July 2022.

Photokeratitis. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. March 2024.

Radiation retinopathy. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. October 2023.

CMV retinitis. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. November 2023.

Leukemia. Cleveland Clinic. May 2022.

Retinitis pigmentosa. National Eye Institute. November 2023.

Commotio retinae. EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. April 2024.

Get a dilated eye exam. National Eye Institute. May 2021.

Page published on Thursday, November 12, 2020

Page updated on Tuesday, August 20, 2024

Medically reviewed on Monday, June 24, 2024